Last weekend I made a trip to Toronto to see the Colville exhibit. A week later I’m still thinking about it and finally constructing a few thoughts into paragraphs. I’m thankful to myself for buying the exhibition catalogue because I had the pleasure of investigating it this morning and taking my impressions a little deeper. Colville, edited by Andrew Hunter (also curator of the exhibit) is not just a pretty art book to look through. It’s well written and thorough and very personal. Which is what happens I think when you investigate Colville’s work.

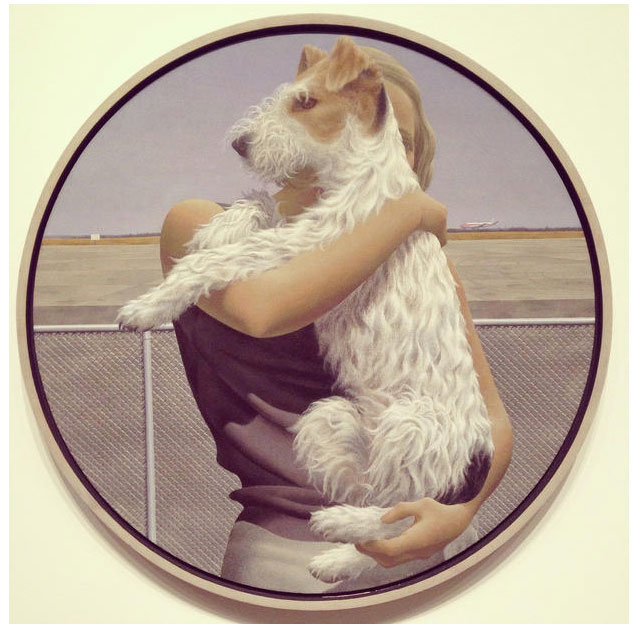

The exhibition is extensive for one man. 5 main sections full of some 170 paintings, drawings, sketches and prints. But Colville worked until the very end of his life at ninty-two (July 2013) without any breaks in his career. In Dog with Bone, 1961, there is a quote from Colville beside the work: “Someone I respect once said that I work like a dog chewing a bone; I consider this a compliment”.

Andrew Hunter did an excellent job of creating context – the pairings with literature and film explains how deeply engaged Colville was with the broader culture – making imagery that would communicate and be meaningful to everybody. The addition of iconic names like Alice Munro, Anne-Marie MacDonald, Sarah Polley, Cormac McCarthy, Wes Anderson, and Stanley Kubrick made the exhibition weighty, gave a deeper understanding and appreciation for the work, thereby heightening the experience.

I think what sticks with me most when I think about the overall exhibition, is the life-time of dogged investigation. He questions the everyday moments of human existance like a philosopher, arrives at some conclusion, and puts together a peice of work that speaks to it. This is obvious in his meticulous sketches and brush marks – he works at creating an image like a surgeon. Revisions, calculations, notations, and manipulations – until he has given you exactly what he wanted you to experience.

(I just lifted my head towards the window, and am caught in a “Colville moment”, where mist is literally rolling from east to west and then stays still. It’s the sense of “suspension” that does it)

In his images, he is re-arranging the world we know but authentically, so that it is belieavable, relatable. We become the girl on the horse looking back at the memorial, we are the man caught up in thought looking at the Pacific with the gun on the table, the soldier leaving (or reuniting) with his lover at the station. He directs the image like a filmmaker (and they are like film stills) manipulating real moments to convey his concept, what he has wanted you to feel/think/experience. When I stand in front of a Colville, it is such a visceral experience, it is as if he has put his hands on my shoulders and directed me there, forcing me to pause for just a minute and the Colville moment envelops me.

(Later when I look up again, the fog is dense. In the foreground mist cascades to the ground. In the background, each particle holds a bright, warm, white light so that the sky is glowing between the trees in a way that a good watercolour can.)

His mind must have been filled with images – memories of moments in his time. He draws on these and manipulates them to create a metaphor for something that is unclear to me, which I can feel instead of know. Wait, there is one thing I know for sure. That there is vulnerability all over the place. A universal condition we are all deeply familiar with, and what makes his work so moving and emotive.

On page 29, Hunter ponders Dog in Car, 1999. He says,

Colville again reveals his depth of engagement with the everyday, his crititcal probing into apparently unremarkable moments, yet at the same time exposes an incredible vulnerability. It is hard to imagine many people going where Colville goes in contemplating a dog in a car and then expressing it with such logic and honesty.

I am so grateful to the Art Gallery of Ontario, the National Gallery of Canada and the Musée des beaux-arts du Canada and especially to all the private collectors who lent the work for the exhibition. As someone who worked at a gallery, I understand how most people don’t get a chance to stand in front of works like these – they quickly get snapped up by collectors often before the work is even exhibited. On top of that, people who don’t live in big cities are sometimes not even aware these exhibtion openings are even happening because the galleries who hold them aren’t able to market to a wide audience. So it’s important that museums and major art galleries put on these traveling exhibitions to get to everybody, not just the art world. So go see it! And buy the book.